|

|---|

|

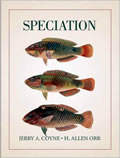

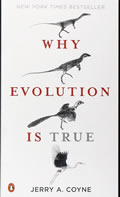

I suppose it started with my father, who was a diehard animal lover. He took me to zoos when I was a child, and also bought me a lot of science books, like the Golden Book of Dinosaurs. Eventually I settled on biology as my favorite topic, but I didn’t settle on evolutionary biology until my second year in college, when I took courses in both evolution and genetics. In fact, that’s when, though I didn’t know it at the time, I was on the path to become an evolutionary geneticist. Almost everything when I was younger. Even if a teacher wasn’t that inspiring, I always managed to find inspiration in the subject itself—even math. It wasn’t until I got to college that I realized I found the greatest satisfaction in studying biology. At first I intended to become a marine biologist—as many nearly all biologists do when young, for it conjures up visions of standing on the bow of a ship watching whales. Eventually, though, I was seduced by the beauty of evolution and the cleanness of genetics. We always had cats, so I suppose that’s one reason I’m enamored of them. My father also had fish and gerbils, but the cats were far more interesting. There were two main ones. The first was Bruce Grant, my undergraduate adviser at The College of William and Mary, whose teaching style and enthusiasm contributed massively to my love of genetics and evolution. For a professor at a small, liberal-arts teaching university, Bruce has produced an inordinate number of professional evolutionary biologists. The other was Dick Lewontin at Harvard, who was not only immensely supportive, but set a great example for ethical behavior in science (e.g., he taught me not to slap my name on my students’ papers). It was a bit arcane. One of the perennial areas of interest in evolutionary biology is the amount of genetic variation in natural populations, for that variation is the raw material of evolution. And we want to know not only how much variation there is, but why it’s there in the first place. Why are there so many variant genes floating around in natural populations? When I did my thesis (1973-1978), the only way to measure that was via gel electrophoresis, which separates different forms of a protein produced by mutations at the gene producing that protein. What I did was refine those methods, and found that traditional methods of electrophoresis didn’t reveal a lot of genetic variation, which could be uncovered only by using multiple gel-running conditions: gel concentration and pH. Moreover, my expanded methods showed that related species became more differentiated than previously known. My results increased the number of known variants by several fold, but that only exacerbated the problem of explaining why so much variation is hanging around in nature. Now gel electrophoresis has been supplanted by DNA sequencing, which is rapid, cheap, and far more accurate. My first job was at the University of Maryland, where I taught general evolutionary biology; and I continued teaching that topic to undergraduates when I moved to the University of Chicago in 1986. I’ve taught evolution, then, for over thirty years (I retired 18 months ago), and it was teaching that course that led me to write my first trade book, Why Evolution is True (see below). Well, I always used fruit flies (Drosophila) to study speciation, because you can not only do genetic crosses between closely related species of flies, thus uncovering the evolutionary and genetic basis of species differences and the reproductive isolation that separates species, but also because they have a short generation time: about 12 days. It was that research, as well as my reading on speciation in general, that led to my first book. Speciation was, by the way, coauthored with my first graduate student, Allen Orr, and was aimed at graduate students and professional evolutionary biologists. I wouldn’t recommend it for people who haven’t had much training in biology!

When I started writing my first evolution course at Maryland, I wanted to begin by telling the students why we know that evolution is true. If they were to remember anything from my course, I thought, it should be that evidence, for among all scientific ideas, evolution is the one most rejected in America. (Polls show that over 40% of Americans are young-earth creationists, completely rejecting evolution, while only about 20% accept evolution as the naturalistic process that science knows to be true.) When I looked around for a discussion of that evidence, though, there was none to be found. True, biology textbooks from the 1920’s did lay out that evidence, for evolution was still controversial at that time, but now nearly all textbooks take the evidence for granted and don’t give it to students. (Likewise, chemistry textbooks and courses don’t begin by giving the evidence for atoms.) When I didn’t find a recent book giving that evidence, I had to dig it out myself, and found that a lot of additional evidence had accumulated in the last 100 years, especially from molecular biology and the fossil record. And that recent evidence had not been summarized in any one place. A friend who was a biology editor at Oxford University Press suggested that I write a “trade” (popular) book on the topic. I was reluctant to do that, thinking that there would be no interest, but in fact Why Evolution is True sold very well, even nosing briefly onto the best-seller list of the New York Times. It continues to sell to both the public and to students at colleges and high schools, some of whom require it in biology courses.

There are many reasons, but I will give four. First, it is the true story of our origins, in contrast to the many mythologies that have been promulgated over the ages. Second, it shows how a simple, blind, materialistic process—natural selection—has led to the appearance of all the remarkable adaptations of plants and animals that used to be explicable only by invoking God or some “designer.” To see an animal like a woodpecker, for instance, and realize that every one of its adaptive features—beak, claws, feathers, and behavior—was a product of this process, is a truly mind-altering experience. So understanding evolution materially increases your awe and wonder at the Universe. Third, evolution shows us that we’re related to every other living species, and also that we’re all equally “evolved,” in the sense that all as our lineages have been around for exactly the same length of time. That realization, I think, gives us not only increased empathy for other creatures, but an impetus to try to preserve all those wondrous products of evolution. Finally, evolutionary biology altered humans’ self-image, showing that we are not the special objects of some creation, but evolved in the same way as all other creatures. True, we are special in the sense of having bigger brains, language, and culture, but those too are partly products of natural selection.

I think the main reason is not, as some maintain, because evolution isn’t taught very well or presented very often. It is! Remember that we’re living in the age of Steve Gould, Richard Dawkins, David Attenborough, E. O. Wilson, Jared Diamond, and so on—all master presenters of evolution. Knowledge of evolution, and smart people who teach it, is everywhere. The main reason the public is so resistant to evolution, and knows so little about it, is because America is so religious, and virtually all the objections to evolution are based on religious belief. (I know of only one creationist among the thousands I’ve heard of who isn’t religious.) America is in fact the most religious of all First World countries, which explains why we’re the most evolution-denying First World country. If we really want to increase acceptance and appreciation of evolution in this country, we have to either convince religious people that their beliefs are compatible with evolution (which is hard), or wait for America to become more secular, which is in fact happening. I actually wrote an essay about this, or rather, a letter addressed to Charles Darwin telling him what happened to his theory in the years since his death in 1882. I did this at the request of Oxford University Press, in honor of the 200th anniversary of Darwin’s birth, which was 2009. Rather than repeat what I said there, you can read what I’d say to Darwin here: https://blog.oup.com/2009/01/darwin_letter/ The letter contains a description of things he’d gotten right in his 1859 book On the Origin of Species, some of the things he got wrong, and a list of recent developments in evolutionary biology that, I think, would have pleased him. That’s a hard question, as I read widely and have favorite books in all areas. I’ll just divide them into four groups. Among popular science books, Darwin’s The Origin of Species is up there, as is Carl Sagan’s The Varieties of Scientific Experience, Richard Dawkins’s The Selfish Gene and The Blind Watchmaker, Jim Watson’s The Double Helix, Horace Judson’s The Eighth Day of Creation, any of the many collections of essays by Steve Gould (I’m not so keen on his non-essay books), and the best natural-history book ever: The Peregrine by J. A. Scott. It’s hard to name my favorite nonfiction books, but they’d surely include the two greatest biographies I’ve read: The Last Lion, William Manchester’s unfinished trio of books on Winston Churchill, and Robert Caro’s The Years of Lyndon Johnson, which is now up to four volumes with one more to come. Other favorites include Isak Dinisen’s Out of Africa, Lytton Strachey’s Eminent Victorians, Tom Wolfe’s The Right Stuff, Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood (if that can be considered nonfiction!) And the hardest group of all: fiction. My favorites include Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, James Joyce’s novelette The Dead, the short stories of Ernest Hemingway as well as his novel The Sun Also Rises, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby and Tender is the Night, Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita, Paul Scott’s Raj Quartet, along with its sequel Staying On, and more recently Pat Barker’s Ghost Road Trilogy. I’m not sure whether poetry counts as fiction, but my favorite poets include Yeats, Dylan Thomas, Sylvia Plath, Keats, and Eliot. Well, for scientists of the past I’d have to place Darwin in there, as I consider him and Newton as the greatest scientists of all time. Other evolutionists and geneticists I admire—who are no longer with us—include Thomas Hunt Morgan, Alfred Sturtevant, Theodosius Dobzhansky (my academic “grandfather”), Bill Hamilton, and Ernst Mayr. “Admire” is a bit ambiguous, as some of my best friends in science, and the nicest scientists, aren’t necessarily the most accomplished ones. But for a combination of accomplishment and level-headedness I’d include, among scientists I’ve known, my Ph.D. advisor Dick Lewontin, the late evolutionary biologist John Maynard Smith, the entomologist and evolutionist E. O. Wilson, the evolutionary ecologists Peter and Rosemary Grant, and the population geneticists Brian and Deborah Charlesworth. Both of the latter couples often publish as a team, and thus their accomplishments are impossible to separate.

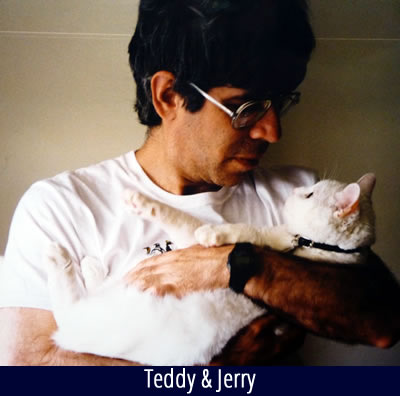

Cats! Cats of all sorts, from the wild cats like the tiger, manul and sand cat to the domestic cat, several of which I’ve owned. Though house cats are “domesticated”, they remain sufficiently wild and natural that their behavior is fascinating to a biologist. And they’re also among the most graceful of mammals; I see them as living sculptures. I would have to say India and Nepal. Both countries have a culture that is about as different from American culture as you can get, and so one can immerse oneself in a completely novel experience: the food is different, the clothing is different, the music is different: everything is novel to an American, but also wonderful. The colors, odors, and flavors of India enchant me: I’ve been there about a dozen times. Nepal is stupendous for its mountain scenery. Once you’ve seen the high Himalayas, and by that I mean Mount Everest and the other 8,000-meter peaks, every other mountain in the world looks tiny. Himalayas peaks soar up near the sun, and being among them is truly the kind of “spiritual” experience—that is, a form of awe that stirs the emotions—that even a nonbeliever can have. This refers to an experience I had in Costa Rica in 1973, when I took a course in Tropical Ecology. While staying at a field station in the dry forest, a mosquito bit me, and happened to be carrying the eggs of a botfly. These flies lay their eggs on a mosquito, using that mosquito as a vector to carry its eggs to the next host: a mammal. In this case the mammal was me, and over a period of six weeks or so, the botfly larva, which had burrowed into my head, grew into a ping-pong-ball-sized lump sitting between my skin and my skull. Rather than have it removed, which is a dicey thing to do (if you break the larva it can infect you), I allowed the larva to exit, hoping to rear it into a fly. Sadly, it died. But you can hear the whole story in an National Public Radio “Radiolab” story narrated by Robert Krulwich. It’s at this site, and my story starts at 46 minutes in: http://www.radiolab.org/story/91672-yellow-fluff-and-other-curious-encounters/ The story of my botfly also appears in the book Tropical Nature, written by two of my graduate-school friends, Ken Miyata and Adrian Forsyth. There are three. They include the Richard Dawkins Award for raising public consciousness about evolution and atheism, the Freedom from Religion Foundation’s Emperor Has No Clothes Award for speaking truthfully about religion, and—an odd one—the Discovery Institute’s “Censor of the Year” award for 2014. The Institute is devoted to promoting Intelligent Design, a form of creationism, and they gave me a mock award for stopping the teaching of Intelligent Design at Ball State University in Indiana, a public college. They intended the award as criticism, but I was quite proud of it! Oh, there are many good parts. My daily posts force me practice my writing, and to learn to write well but quickly—a prerequisite for working on deadline. The site also allows me to share my knowledge of evolution (and many other things, including food and travel) with an audience of nearly 53,000 people, that helps me get feedback on my ideas from a vast and diverse audience. In fact, without that feedback, which stimulated my thinking, I wouldn’t have been able to write my second trade book, Faith Versus Fact. Finally, it’s allowed me to make friends with many people throughout the world, some of whom I get to meet on my travels. I think of the website not only as an extension of my character, which I express through what I write and think about, but also as a large living room: a salon full of diverse conversations. Right now I’m finishing an unusual project—a children’s book based on a man I knew in India, an interesting character who is runs a sweetmaking operation and also is an animal lover, owning about fifty cats. After that I plan to write a short popular book on speciation, since none is available. And, if you consider this a “project,” I want to do a lot of travelling, since there’s a lot of world to see before I die. In the next year I’ll be going to New Zealand, Mexico, Canada, India, and Australia, and I am hankering to visit Antarctica and Southeast Asia.

For more information, please visit Jerry's blog: Why Evolution is True For more information, and to buy Jerry's books:

Interview by: Nicole Reggia |

INTERVIEW with Jerry A. Coyne, Ph.D

INTERVIEW with Jerry A. Coyne, Ph.D

What inspired you to write your second book, Why Evolution Is True?

What inspired you to write your second book, Why Evolution Is True?