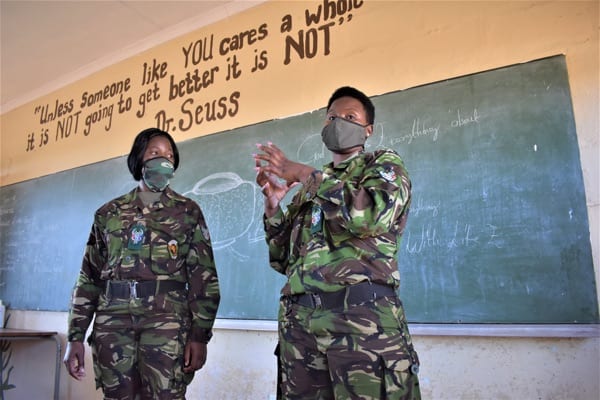

*Photo credit: Transfrontier Africa NPC (Belinda is second from the left) |

|---|

|

I heard about The Black Mambas Anti-Poaching Unit from one of my friends in March 2014. She told me that they wanted more women to join the team. I was part of the second recruitment. I submitted my CV and they called me for an interview. When they selected me, me and other women went for training at the Pro-Track Anti-Poaching Academy. The training was difficult. We did PT, learned about the Bush, animal behaviour, and the patrols. When the training was done, I was deployed as a Black Mamba ranger. People can help through donations and spreading the word. We are always in need of donations, car spares, service and equipment. We rely greatly on donations because The Black Mambas is run by the non-profit organization Transfrontier Africa NPC. Media crews that come to work with us make documentaries about our work and life. Photographers and writers interview us and publish articles in their magazines. All this is to tell the world what we do for our wildlife in South Africa, and spread our message across the globe.

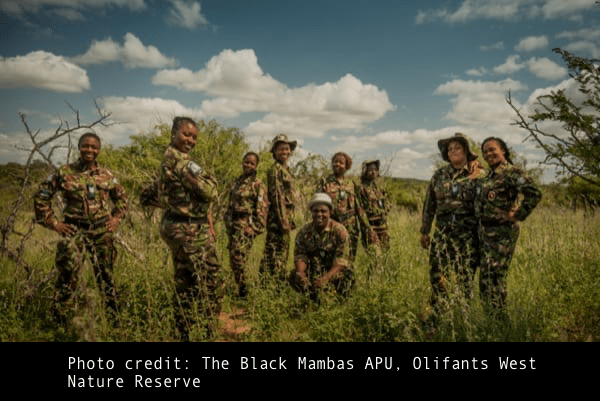

Subsistence poachers are the people who simply need to eat. If they do not have means to support themselves and their families, they will most likely poach. It is no coincidence that bushmeat poaching had increased by at least 6% in our reserve during the pandemic, as many people lost their jobs. Commercial poaching, on the other hand, is a far more complicated case. Too many role payers involved and the reason for poaching here is a Chinese demand for rhino horn and other animal parts and greed of the people who do the dirty job. If the poachers keep on killing the wild animals in our reserve and elsewhere, there will be lack of job opportunities in sectors like tourism and other nature/environment related industries. Yes, our families are very supportive when it comes to work, and they are proud of us. When we started operating in the Greater Kruger Area, many people thought we cannot do this job because we are women, because this has always been a man’s job. But we proved them wrong. Our sister project (The Bush Babies Environmental Education Program) is operating in ten local rural schools nearby in The Greater Kruger Park. We regularly join Environmental Monitors who run this project at schools to tell the kids about how important it is to protect animals. The most rewarding part is when we remove the snares that were set by poachers. Then I know we have saved animals’ lives. Three weeks at Pro-Track, plus several months in-house training; so it makes six months in total. Sometimes I do feel scared when we see the tracks of poachers, because we never know how they will behave. I did not really know a lot about nature as I was growing up. But when I became a ranger, I took a specialised course; Unarmed Field Ranger at South African Wildlife College.

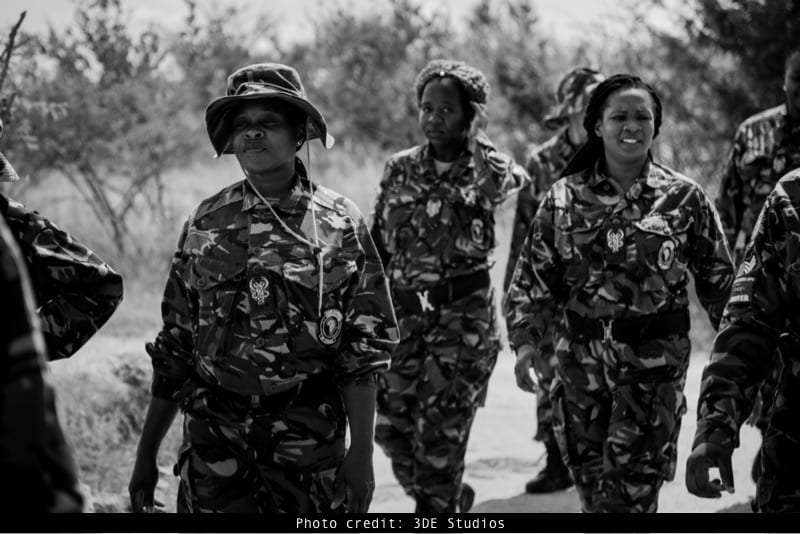

The Black Mambas are the eyes and ears of the reserve and we are unarmed. Our tactics are visual policing, early detection, reporting, and gathering the information that helps intelligence and investigation. Our goal is not to catch the poacher inside the reserve, although that does happen, but to prevent poachers from coming into the reserve, which is a much harder thing to do. Constant presence is our tool. We use our tracking phones with a special software for data collection, and radio phones to report the findings and suspicious activities to our ops room. Our work has had a big impact on conservation of nature, and people. The whole innovative approach, where we merge boots on the ground, education, building relationships with communities, food security parcels during the pandemic, empowering young people and women from our communities. We do see the change in people’s mindsets about poaching and women’s role in tackling it. Now people in communities are helpful and supportive.

When poachers are caught, we arrest them. After that they get detained. We immediately report it to the ops room and the ops room managers send the response team, and the police. After that they get detained. We wait for the further investigation, apprehending and statements to be done. After that the court takes place, and the poacher is convicted.

For more information on The Black Mambas: Visit Black Mambas page Interview by: Nicole Reggia |

INTERVIEW with Belinda Mzimba

INTERVIEW with Belinda Mzimba